Student Study Group Researches The State of Cheating

June 4, 2014

Has this ever happened to you? Your teacher hands out a test that you had absolutely no time to study for, given your millions of extracurriculars and sports games. You stare at the garbled writing on the page, and your eyes flit nervously across the room. Your palms are sweaty, you are breathing heavily, and panic emanates from all around. You have to keep your A grade for the year, so you resort to your only logical choice. Your eyes dart towards your neighbor’s paper…

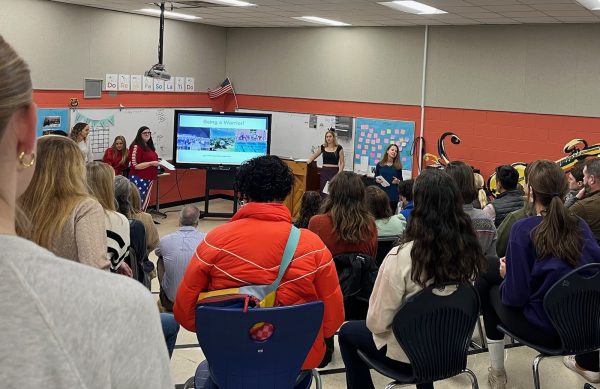

Seniors Allyson Barkley, Leila Bushweller, Hannah Epstein, Sophia Loman, Andrea Garcia and junior Chance Masloff conducted a study to measure the amount of cheating at Western.

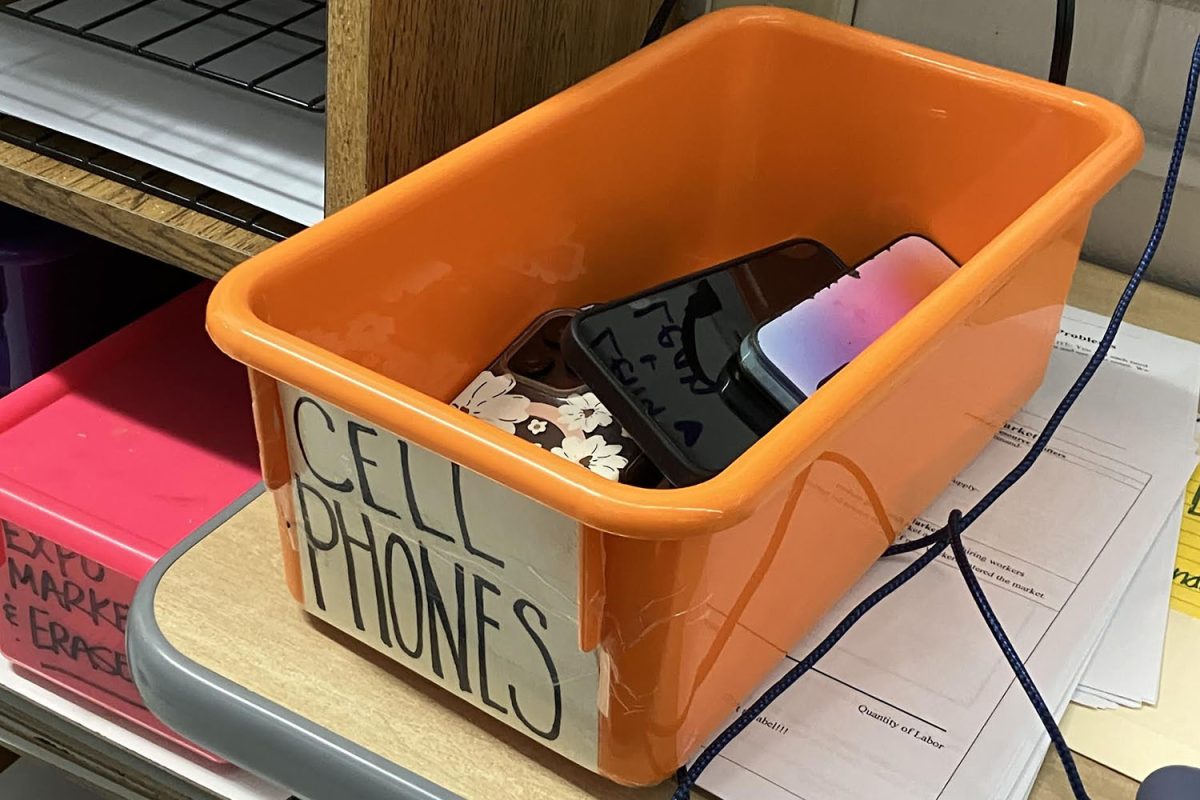

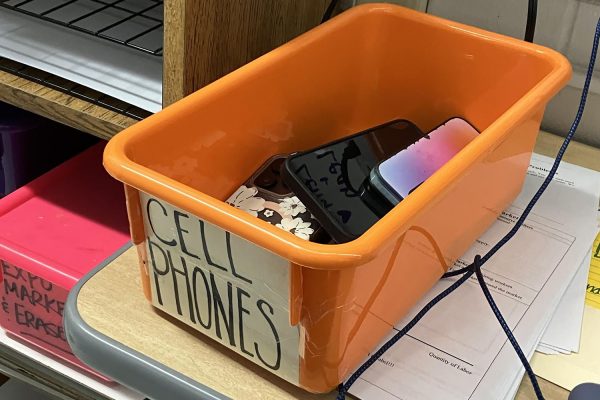

Cheating is when people act unfairly in order to gain an advantage. It can be disguised in various forms: scanning your phone during a quiz, peering over at your neighbor’s paper, finding out about test questions even before the actual test, etc.

First, they sent out a survey asking students if they had ever cheated, how often, and if they thought it was a problem. They received 142 responses, from students of all grades. 59 percent thought cheating was a problem. 55 percent admitted to having cheated in high school.

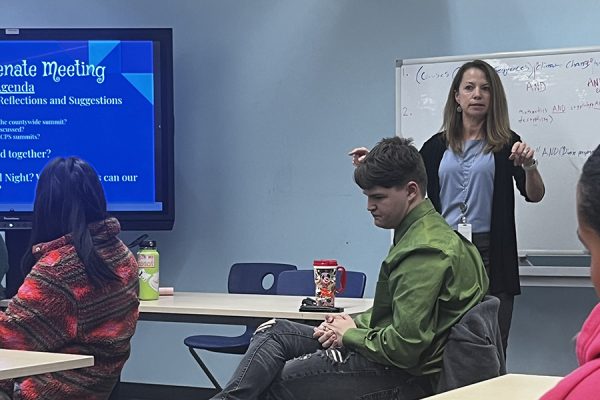

After tallying these results, they sent a similar survey to the teachers.

For the most part, the teachers believed that their own students cheated more than WAHS students as a whole. The most significant finding from the teacher survey was that the teachers are not doing enough to prevent cheating.

87 percent of teachers claimed that they walk around the room during assessments. 65 percent also said that they remind students about cheating and discuss meaning and consequences.

“From experience, our group does not believe this data to be true. This is either an exaggerated statement or it is not being done effectively,” Barkley said.

On another note, 78 percent of teachers reported that they very rarely or never send students to administration, where they have the opportunity to go before the Honor Council, in cases of cheating.

The data from the survey made the group question the effectiveness of the honor council.

“Although our honor code is a good concept, outside research has shown us that schools with honor codes are not necessarily less prone to cheating than schools without,” Barkley said.

“The main factor that can prevent cheating is instilling an anti-cheating culture,” the group remarked in their report. Both students and teachers reported competition for grades as the main reason for cheating. Western students are very high-achieving and very competitive. With little punishment for cheating and a lot of pressure to get the grades, students often feel that cheating is a low-risk, high-reward option.

The group designed an experiment to imitate a natural classroom environment that would allow students to cheat with little risk of punishment.

“We brought in several high school-aged friends from outside Western to pretend to be AP Psychology students making up a reading quiz during lunch. The classroom had four students: the fake quiz-taker, one student tutoring another, and one student listening to music and taking notes. The subject was invited into the room to take part in a fake interview about stress, conducted by one of our group’s members. After asking the first question, she left the room to get a paper she had “forgotten” and remained out of the room for 45 seconds,” Barkley said.

During their simulation, the quiz-taker asked the subject for help, saying she had not finished the reading. Then, the subjects’ responses were recorded.

In the experiment, 36% cheated although only 23% said they would in the previous survey.

“There was a strong trend of younger students helping more than older students. Our group concluded that this was because the younger students did not understand cheating as well,” Barkley said.

After analyzing their results, the group concluded that cheating mostly occurred using technology and discussing questions between classes.

“Curbing the cheating at WAHS will take a bigger change in culture that needs to begin with harsher reaction and response and commitment from students, teachers, parents, and administration,” Barkley said.

The group believes that teachers could emphasize the definition and consequences of cheating more strictly, and explicitly state their expectations for specific assignments.

They hope that with more attention towards these problems, the combined efforts of teachers, parents, and students can together deter cheating at WAHS.