Students Must Learn the Hard History of their School Systems

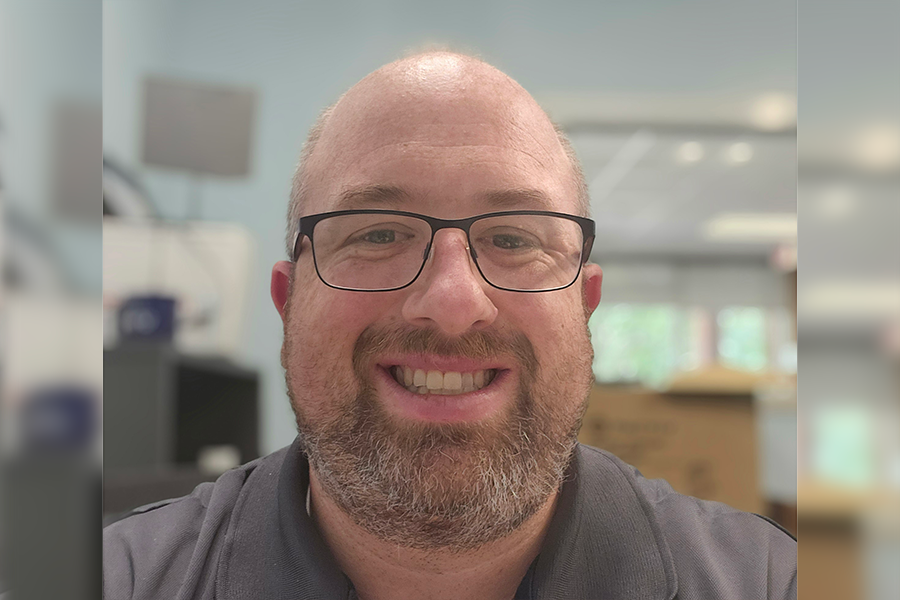

Credit: The Daily Progress

Student Sandra Wicks, a member of the Charlottesville Twelve, enters Venable Elementary School on September 8, 1959.

June 4, 2021

The Anti-Racism Policy, adopted by Albemarle County in 2019, recognizes that “educators play a vital role in reducing racism and inequity by recognizing the manifestations of racism, creating culturally inclusive learning and working environments, and dismantling educational systems that directly or indirectly perpetuate racism and privilege through teaching, policy, and practice.” The district recognizes that building a climate for people of color, who have been historically marginalized, is essential to an inclusive and equitable learning environment. The first step in creating this environment is recognizing Virginia’s long history of defying integration, as the dominant caste attempted to maintain supremacy. This is that history.

The 1954 landmark decision in Brown v Board of Education ruled unanimously that the segregation of public schools was inherently unequal. The majority opinion, read by Justice Earl Warren, stated that schools should move forward with integration with “all deliberate speed.” However, this vagueness allowed Virginia segregationists to resist the ruling and organize resistance.

In response to the ruling, the 1956 Virginia General Assembly established the Pupil Placement Board, charged with assigning students entering the school system or seeking a change in public schools. The Board took into account students’ health, aptitudes, transportation needs, and issues they deemed “pertinent to the efficient operation of the schools or indicate a clear and present danger to the public peace and tranquility affecting the safety or welfare of the citizens.” In other words, the Pupil Placement Board took into account attitudes, transportations needs, and race. Throughout its three-year existence, the Pupil Placement Board oversaw approximately 450,000 applications yet did not permit a single Black student to attend a ‘white’ school.

Virginia segregationists then stepped up their game, using Massive Resistance, a strategy used across Virginia to block the integration of public schools. In his Southern Manifesto, former Virginia Senator and Governor Harry F Byrd condemned the Supreme Court’s decision as a blatant violation of states’ rights, writing that “If we can organize the Southern States for Massive Resistance to this order I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.” In 1956, the dominant political machine known as the Byrd Organization passed a series of laws known as the Stanley Plan, which restricted integrated schools from receiving state funding and extended power to the governor to shut down any such school. Segregationist-elected officials would go so far as to compromise the education of all students to preserve preeminence.

In 1956, after a suit by the NAACP and Charlottesville parents, US District Judge John Paul ordered the Charlottesville School Board to commence with integration. In response, the governor shut down Charlottesville schools, as permitted by the Stanley Plan. Schools were closed until February of 1959, following a ruling by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals that Massive Resistance was a violation of the State Constitution.

Charlottesville City Schools were not integrated until September of 1959 when Judge John Paul ordered the immediate transfer of twelve African American students in Charlottesville. These students, now known as the Charlottesville Twelve, were the first to integrate Lane High School and Venable Elementary School three days after Judge John Paul’s ruling on September 8, 1959.

As courts across the state overturned Massive Resistance policies, and the era of “passive resistance” began. Passive, not meaning non-violent like the methods used by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, but meaning less explicit. Although the government could not explicitly prevent a Black student from petitioning to attend a ‘white’ school, the goal of “passive resistance” was to redline Black students into their original schools.

In anticipation of the required integration of schools, Virginia invested more money in schools in the 1950s and early 60s than at any time in its history. Jackson P. Burley High School, now known as Burley Middle School, was in part, a product of this influx of cash. Jackson P. Burley High School consolidated the districts of three other high schools and upgraded features to ensure that students did not integrate the surrounding area, a common practice of “passive resistance.”

In 1963, nine years after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, 26 Black students from Albemarle County integrated Greenwood School, Albemarle High School, and Stone Robinson Elementary School. 14 of the Albemarle 26 were wrongfully forced to repeat a grade.

Charlottesville, the urban center of Albemarle County, received more public scrutiny for its policy of massive resistance, while the practices of “passive resistance” in rural Albemarle slipped by relatively unnoticed. As a result, there is limited information about Albemarle integrated four years after Charlottesville and there is limited documentation of that history.

The importance of discussing hard history is undeniable. Doing so makes us aware of the cultural significance of the past, its ramifications in the present, and empowers us to engage and address the challenges of our future. As Fred Shuttlesworth, a founding member of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, once said, “If you don’t tell it like it was, it can never be as it ought to be.”

To learn more about this topic, check out local filmmaker Lorenzo Dickerson’s documentary titled “Albemarle’s Black Classrooms,” available here.

Sources:

- https://www.cvillepedia.org/Charlottesville_Twelve

- https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=lva/vi02003.xml

- https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/massive-resistance/

- http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/civilrightstv/glossary/topic-017.html

- https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-era-massive-resistance