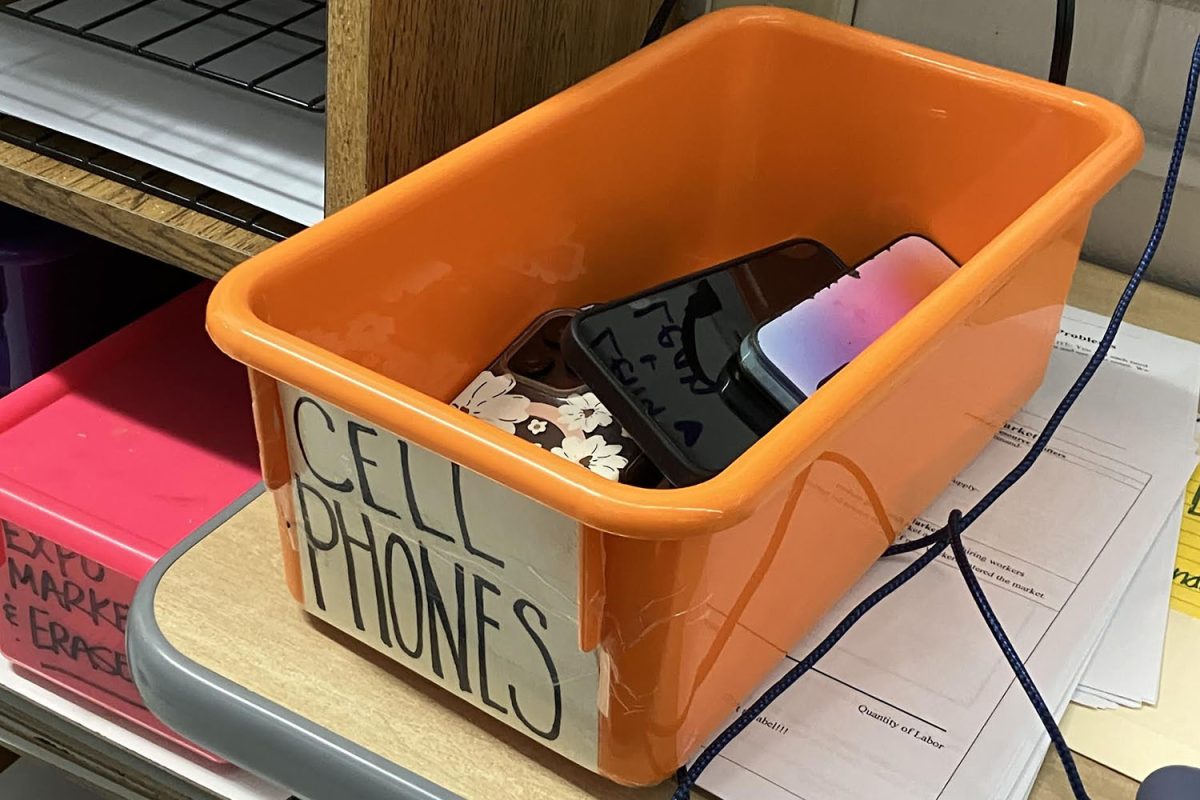

It’s the fall of 2023. Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is taking the world by storm and The Barbie Movie just debuted and cured sexism. A scorching summer is over and it’s time for back to school. As students unknowingly run back to class, something major has changed at Western. In each classroom, they are greeted with shiny, numbered plastic pockets and an expectation that they surrender their phones at the beginning of class. After a year of a lax away-for-the-day policy, it seems that ACPS is finally walking the walk and talking the talk— taking systematic action to reduce distractions in schools.

Predictably, this new strategy of implementation received significant backlash from students who were used to working around the prior ban’s lenient enforcement. Now a full semester later, we can look back on this policy and evaluate its successes and failures through a critical lens.

Although Albemarle County has boasted a cell phone policy for years, the beginning of the 2023-2024 school year brought with it a much more robust system. Students were expected to have their phones off and away during class time, including during bathroom and water breaks. However, the keystone of this initiative has always been the teachers, who are responsible for enforcing the policy within the classroom.

So what exactly is the phone policy trying to instill in students? Some see it as another aspect of education entirely. “Many of my AP level students are going to college, where enforcement is voluntary, so they should be learning self-control now,” said Carol Stutzman, a science teacher. “I think kids mature throughout high school, but whether or not they choose well, I still have to teach them.”

To some, however, the backlash the phone policy received and the goals of the policy itself are two sides of the same coin. Basically, if students weren’t using their phones during class, then it stands to reason that they wouldn’t mind putting them away in backpacks for the period.

“I do think it’s an addiction,” explained Susan Lohr, in regards to the role of cell phones in students’ lives. “We’re dealing with something more than people not complying; we’re dealing with some sort of psychological addiction.” Looking at the policy through that lens, the backlash the policy received was inevitable.

So what does the school do to support the phone policy in the classroom? In theory, it was supposed to be a lot. The school was “going to do a lot of things that wouldn’t have been on [teachers] plates at all.” explains Stutzman. In the original plan, punishments for phone use would be handled by the front office, who would call parents or confiscate a student’s phone after a number of infractions. However, the follow-through on this policy has been lackluster. “I know of one case…where a kid told me [the front office] had his phone,” Stutzman continued, “I know there’s a lot more offenders than that.”

However, both teachers interviewed agreed that the policy was at least partially effective. “It’s way better than it was,” commented Stutzman. “I think we’re taking a step in the right direction,” said Lohr. Although they both agreed that the cell phone issue isn’t completely solved, they could both see a significant improvement from previous years.

With all that said, does everyone agree that the cell phone policy was effective? It may not be that simple. Although the teachers interviewed seemed to agree that the cell phone policy was overall a force for good in the classroom, students had the opposite reaction. In an admittedly informal survey, I asked some students I sit near in my classes, “Do you think that the cell phone policy effectively limited the influence of cell phones in the classroom?” 68% of the 25 juniors and seniors polled answered “no,” while only 16% decisively answered “yes.” So why do the majority of students think that the policy failed? Some students believe that the policy is imperfect in the first place. “Responsible students can work without being entirely distracted by their phones, while irresponsible students may be too distracted,” explains junior Mack Whiting “I think the policy fails to address that.”