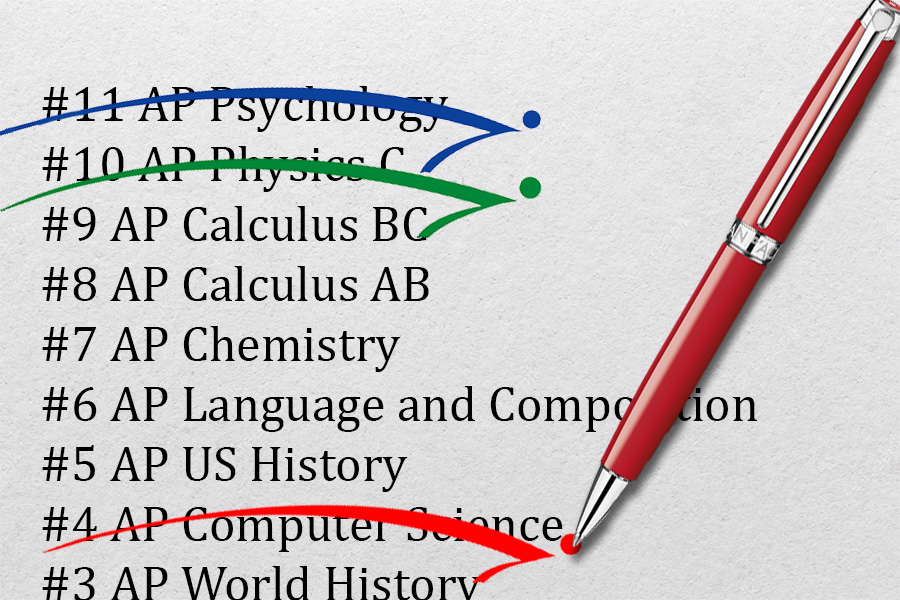

Last year, Albemarle County Public Schools adopted a new set of rules around taking AP classes. These new regulations removed APs as an option for freshmen, so this year, as sophomores, they are just now feeling the other effects. The centerpiece of the new rules, though, is a hard limit of 9 AP classes throughout each student’s high school career.

However, not everyone is feeling the change. Freshman Colin Rutherford said the changes didn’t affect his academic plans at all, a sentiment shared by fellow freshman Tessa Showalter. “I feel like that’s what I would do anyway,” Showalter said about the AP limit. “I wouldn’t take more than three in a year.”

Some, like freshman Braden Clarke, even appreciate the new rules. “AP classes give you a really high advantage,” he said, “but having different levels is important.”

Others will miss some of the advantages that come with AP classes. Freshman Blythe Sturman said, “I would rather they not, because I feel like it’s harder to stand out to colleges” without taking many APs. Others, like sophomore Annie Alhusen, agree. Alhusen said, “It shouldn’t be a rule, because it limits the classes you’re interested in.”

Freshman Anna Pinto agreed. “I think if a person is able to handle the amount of APs, if they understand what they’re getting into, it should be their choice.” She says the AP limit has shifted her academic priorities. “I really have to think about what classes would look good for colleges and benefit me the most.”

For Pinto and other students butting up against the limit, AP electives are the first thing to go. “I was planning on doing some AP electives, but now I won’t because I need to make sure my normal classes are APs,” said Sturman.

But according to counselor Amy Wright, the new policy is actually meant to help high-level electives. “There was a group of students from Albemarle County, years ago,” she said, “who felt they had to take all the hardest classes available, including APs. One thing these kids did was forgo upper level electives.”

She recognized students’ concerns about college, but according to her, “we have this idea that when you select classes, you should look for something that flows your mojo, and you should look for things that look good for college. But really we have it backwards. You should find something that flows your mojo, and then you should look for a college that will feed that.”

Wright shared an anecdote about a student she had worked with years ago. “He took Journalism 1, 2, 3, 4, and that meant that his weighted GPA wasn’t the highest in the class. But he did the class he loved, and he ended up at Yale.”

She dismissed the idea that a cap on APs and therefore weighted GPAs would affect college admissions. “This notion that ‘I have to take weighted classes’ is untrue,” she said. Very few colleges even look at weighted GPAs, she said. Instead of chasing the highest weighted grades, Wright says she wants to see students “taking courses that feed their soul.”

According to Wright, the ultimate goal of the policy is to reduce stress. “That policy was a result of kids feeling stressed out. The impetus for all these changes came from student voices.” She added that the policy was meant to “help students help themselves.”

Many students understand the reasoning, but ultimately some still disagree. “I get what they’re doing,” said Pinto, “but if students can handle the challenge of APs, it really should be their choice.” Sophomore Lucy Coward agreed. “In junior or senior year, I don’t want to be limited to lower-level classes,” she said. “Students should be able to go farther if they want.”

By nature, only time will reveal the full impact of the AP limit on Western’s classes – and the students who take them. Even if the school system’s reasoning is clear, student feelings remain mixed as they move through their newly limited school careers and await the policy’s full effects.